Building history and project details

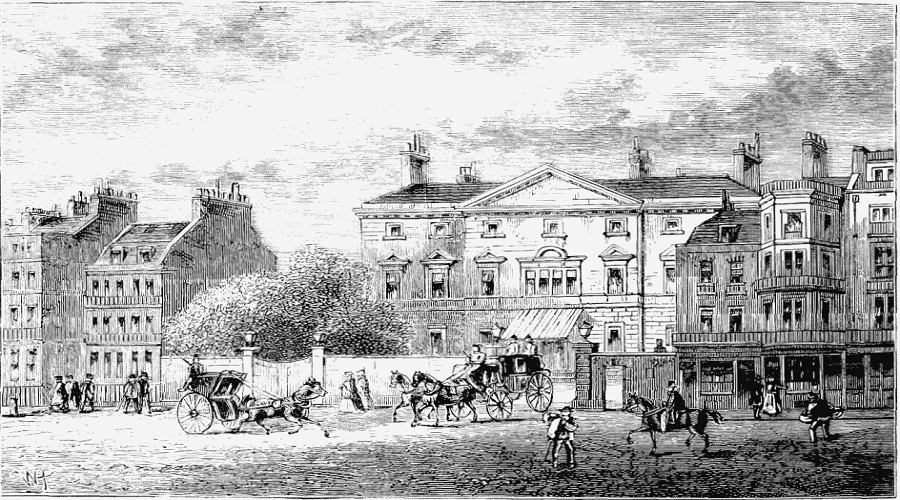

Originally constructed as a residential dwelling, Cambridge House operated as the Naval and Military Club from 1865 to 1999. It has always been affectionately known as the ‘In and Out Club’ due to the ‘In’ and ‘Out’ signs for vehicles passing into the courtyard in front of the building.

Cambridge House occupies a prominent position on Piccadilly, between White Horse Street, Half Moon Street and Piccadilly itself.

Having stood empty and unattended for 20 years, the buildings required stabilisation works before construction and fit-out works could commence.

The scheme

Located on a site which incorporates the Grade II listed 90-93 and 95 Piccadilly, the Grade I listed 94 Piccadilly, as well as properties at 42 Half Moon Street and 10-12 White Horse Street, this 18,000 sq. m. scheme comprises a development of private residences alongside a new hotel with 102 rooms and a 327-cover restaurant.

The consented scheme for 90-93 Piccadilly included the retention of all existing elevations and full removal of the internal fabric, apart from the staircase and landings, which were to be retained. 94 Piccadilly is a Grade I listed building that features ornate fibrous plaster ceilings and protected joinery throughout.

Commissioned by Motcombe Estates to work on this £165 million development, Deconstruct were heavily involved in multiple aspects of the project. A wide-ranging remit extended from enabling and temporary works, significant multi-level subterranean activity and demolition, to alteration of existing structures and the construction of new reinforced concrete above- and below-ground structures. In addition to this, Deconstruct are proud to have played a significant role in the preservation of the historic interiors of the existing buildings.

Conservation works

Working methods were meticulously planned and approved with Historic England by heritage specialists PDP Architects, with movement monitoring regimes implemented to ensure the protection of the listed features.

Prior to works commencing, a painstaking process of cataloguing and recording the buildings was undertaken, with Westminster’s heritage office in attendance for much of this phase. A key objective was the identification of areas that needed removing due to irreparable damage caused by neglect and the ingress of water. PDP Architects oversaw this process, drawing up a catalogue of areas and submitting a number of amendments to Westminster as the building was opened up.

Opening up the building was undertaken as a close, collaborative process between Deconstruct and PDP. Upon finding areas in need of repair, Deconstruct made the area safe, propping it appropriately before enlisting the advice of the design team on how best to proceed.

Some rooms were in an advanced state of dilapidation, such as the Billiard Room, where many joists were rotten and had disintegrated, leaving little to hold the floor in place. Here, we propped the floor and exposed the timbers, allowing for the main Bessemer beams to be repaired by inserting steel rods along their full length and casting new ends to the beams in resin.

Numerous historical features were removed for the purposes of restoration and replacement. From 90-93 Piccadilly, stone elements such as porticos, boundary and façade walls and the cigar bar; from White Horse Street, stone chimney features, timber doors and frames, fibrous plaster mouldings and the stone and brick façade.

In a project rich in architectural heritage, many features are of considerable value. The ceiling to Lord Palmerston’s bedroom at 94 Piccadilly is insured to a staggering £1.7 million. From a conservation perspective, the project also presented significant logistical challenges, including working on the spectacular timber and glass dome at 94 Piccadilly and maintaining the staircase to 90-93 Piccadilly whilst excavating four floors below it.

The latter was achieved by encapsulating the stair in a temporary steel frame and installing steel needles supported on temporary piles at the base of the stair. This temporary frame was then tied into the façade retention. On the lower levels, the piles were tied together at the same level as the proprietary basement propping with a bespoke designed waler. In the completed scheme the existing stair is tied back to the permanent RC slabs with a steel angle to the existing façade.

The Cambridge House project is a case study in balancing the needs of demolition, enabling and temporary works with conservation and heritage considerations. In structures of such historical significance, factors such as vibration need to be taken into account. Accordingly, all demolition work was carried out by hand, rather than with heavy machinery.

Detailed surveys of the existing structures were undertaken before the commencement of any works. In addition to this, monitoring points were attached to the existing external walls with baselines established, enabling any movements in the structures during demolition and basement excavations to be closely monitored on a weekly basis. If movements exceeded acceptable parameters, works were stopped.

As with most projects of this nature, the Cambridge House scheme also unearthed some fascinating historical insights. Excavation works along the front of 90-93 Piccadilly exposed original back yards and footings of the town houses that were demolished to make way for the original construction of Cambridge House in 1760. Uncovering these footings revealed an original brick sewer and artefacts such small knives used for cooking — glimpses into a history that had lain undisturbed for over 250 years.

Works in detail

This wide-ranging project encompassed three distinct categories of work: repair, replication and removal.

Repair

Repair works divided into two categories — retain & repair and remove, repair & reinstate.

The former saw features being repaired in situ where appropriate and practicable, whilst the latter involved items being dismantled and transported to our workshops, including doors and windows in need of upgrading for fire, thermal and acoustic purposes.

Replicate

Original features that were either too damaged or degraded to repair were instead re-created and replaced. After a painstaking process of recording their appearance and physical attributes, these items were dismantled and removed. Faithful replicas were then produced to match the exact dimensions, shape, materials and finish of the original features.

Wherever items were to be dismantled and rebuilt or removed for conservation and repair, they were recorded photographically and by measurements and tagging. Deconstruct made a precise record of the location of each element, to enable the various elements to be replaced in their original locations. A critical consideration in such a historic structure, we held every necessary approval prior to the commencement of dismantling.

Remove

Where appropriate, elements that could not be repaired or replicated were carefully removed from the building to allow for new development.

Transport

All components were transported with appropriate packing to protect against damage, exclude dust, prevent contamination, and safeguard against the loss of loose components in transit.

90-93 Piccadilly

The Grade II listed staircase and façade at 90-93 Piccadilly were retained, whilst carefully dismantling any remaining structures that existed. This painstaking process called for challenging piling work, with piles being installed in narrow corridors and doorways. Upon completion of temporary works and dismantling, the staircase was designed to appear as if suspended in mid-air.

94 Piccadilly

Grade I listed 94 Piccadilly was carefully examined and a meticulously detailed schedule of features produced. As the ground and first floors contained the most significant spaces, with original and 19th century decorations, the adopted strategy prescribed a conservative approach to features on these floors, with a more flexible intervention at levels of lower significance.

Most of the features such as skirtings, cornices and mouldings were retained and repaired. In some instances, where excessive damage or degradation were evident, a replacement to replicate the existing feature was proposed. This sympathetic approach ensured the preservation of the character of the most significant spaces within the new scheme. Mirrors and other readily removable pieces of furniture were carefully removed from the building, repaired and reinstated as valuable assets of the building’s original character.

Basement, second and third floors had a much lower level of significance, with most of the features dating from the 20th century. In order to meet the requirements of a modern 21st-century hotel, most of the features on these floors were therefore replaced with new.

The historic staircase

Matthew Brettingham’s design of the original 18th-century iron staircase balustrade resembles the balustrade he designed at Norfolk House at 31 St James’s Square, Westminster. Completed in 1756 (the same year as 94 Piccadilly, with which it shared a very similar plan) Norfolk House was built for the Duke of Norfolk, remaining the family’s London residence until it was demolished in 1938.

Given its historic significance, it was proposed that the existing balustrade should be replaced with a scholarly reproduction, using records of the balustrade at Norfolk House as a reference. Accordingly, the existing stone treads and side face were repaired to the original 18th-century profile.

95 Piccadilly

In keeping with 94 Piccadilly, the general approach to 95 Piccadilly took into consideration the level of significance of the different spaces and their features. Again, the ground and first floors contained the most significant rooms with the most valuable features.

Learn more about our Cambridge House project.

*imagery copyright:

Carousel, 1) British History Online, available from https://www.british-history.ac.uk/

2) PROJ3CTM4YH3M, available from https://www.proj3ctm4yh3m.com/urbex/2019/02/02/urbex-the-naval-and-military-club-known-informally-as-the-in-out-club-london-june-2017/

Staircase, British History Online, Figure 154b, Norfolk House, St. James’s Square, in 1937.